Is the monitor really that important?

The quick answer: YES, absolutely.

IF YOU CAN’T SEE THE COLOR AND TONAL DIFFERENCES on your monitor, then you can’t make good post-processing decisions and adjustments to your digital negatives. It’s that simple. You can’t adjust your curves to give your print smooth tonal transitions or to distinguish subtle shadow detail if you can’t see those transitions and details to begin with. In order to make optimal adjustments to your digital negatives, you must be able to see as much of your color gamut as possible and the color must be accurate and reliable.

Monitor Technology : IPS vs. TN

TN stands for Twisted Nematic, which is by far the most popular and wide-spread screen technology. If you have a standard or even higher-end “gaming” LCD monitor for your PC, this is what you have (the same is not true for some Macs). TN screens initially gained popularity because of their low energy consumption, but also because of their quick response time, which is important in reducing ghosting and producing smooth motion for gaming and video. Most TN monitors these days advertise response times of 2-6ms , though they are not always measured in the same way, so comparison is difficult. They are also very bright and are being made with increasingly high resolution, so they appeal to most average consumers. They’re also the cheapest monitors on the market.

More importantly for photographers, though, is that TN monitors use 6-bit color technology, and therefore can’t display the full 24-bit color range (16.7 million colors) that video cards can produce (and that the monitor manufacturers usually claim they can produce). Instead, they attempt to simulate the full range of colors by interpolation of other colors, which they do with limited success. Many TN monitors (non-LED) display less than 30% of the NTSC color gamut, and the color that they do display is only accurate when viewed head-on, so the appearance of color shifts when viewed from and angle is dramatic, and problematic around the edges in any circumstances. Improvements are continually being made in TN technology, but they have a long way to go.

IPS panel monitors, on the other hand, have a different set of advantages and disadvantages. IPS stands for In-Plane Switching, although modern IPS panels actually make use of a variety of improved technologies, such as S-IPS, H-IPS, AS-IPS, and E-IPS. Engineering details aside, the main advantages to IPS panels is that they are truly 8-bit technology (or 10-bit), with many IPS monitors producing 125% or more of the number of colors in the NTSC gamut. Second, the colors do not shift when viewed from different angles; most remain accurate well past 170 degrees. But of course, there are disadvantages as well, though they are also improving. Initially, the IPS technology was much slower than TN, with response rates of 20-50ms. This made it unusable for video and gaming. S-IPS and a variety of “turbo” technologies have now improved that rate, and 14ms and faster speeds are common, making them very suitable for video, though still somewhat less desirable for gaming.

IPS monitors have been much more expensive as well, though the gap is beginning to narrow. Even a year ago, the most common IPS monitors (Mac Cinema Displays) cost three times as much as similarly sized TN screens, but now 23″ IPS monitors can be found for as little as $300. Professional graphic arts monitors using IPS and other less common technologies still cost thousands of dollars, though.

S-PVA is another excellent but less common technology. Like IPS, S-PVA panels use at least 8-bit technology, have very good gamut coverage, and colors do not shift when viewed off angle.

Standard Gamut vs. Extended Gamut

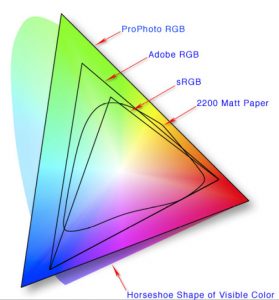

Photo editing monitors can be broken down into two main categories: Standard Gamut (sRGB) and Wide or Extended Gamut. Standard gamut monitors generally attempt to display all of the colors in the sRGB color space, while extended or wide gamut monitors attempt display a larger gamut, such as that found in the AdobeRGB color space.

Most people immediately assume that “more colors = better” and decide that they need an extended gamut display. However, the matter is slightly more complicated than that.

Although extended gamut displays work wonderfully for their specific purpose with programs that support them, they are generally not great for general purpose use. Keep in mind that photos on the internet are virtually all sRGB, and more importantly, our browsers display them as sRGB. When a program’s sRGB output is displayed on a wider gamut monitor, though, the colors can go wild! They frequently shift and become over-saturated, others may look washed out. To deal with this, most wide gamut monitors have separate profiles for different uses, and you need to switch between them depending on what you’re doing, or, if properly set up, a color managed operating system can sometimes switch for you. (Color management is too complex and beyond the scope of an article like this, but a quick Google search will help)

And if you only publish to the web or publish through online printers who only accept sRGB jpgs (as many wedding and portrait photographers do), then there is little advantage to using a wide gamut monitor anyway, since your output is ultimately going to be sRGB.

However, if you do fine art printing at a high quality lab that can accept your files in a wide gamut format (Adobe1998 or ProPhotoRGB) or if you print on a professional quality inkjet printer in your own digital darkroom, it’s worth the effort to use an extended gamut monitor. If you have a workstation that is dedicated to photo editing (or a similar project with the need for wide gamut display), making the decision to get a wide gamut monitor should be even easier.

Which Monitor Should I Get?

The answer, of course, depends on your budget. You can spend anywhere from $300 to $3000 or more. In this case, however, it is a safe bet that even the cheapest options will be dramatically better than what you’re currently using (if you’re using a standard TN desktop workstation screen).

Entry-Level IPS Monitors

On the low end of the price spectrum, Viewsonic has been reliably produced IPS monitors for a few years now. In October 2012, Viewsonic announced 3 new slick-looking IPS panel monitors: the VX2370Smh-LED 23″ and VX2770Smh-LED 27″ models for $ and $, which are available now, and a 22″ model that should be in stores before 2013. These new monitors have very nice, consistent color, and also have a “frameless” design that makes them a little easier to use in a multi-monitor setup. $164 is a great price for the 23″ monitor; only two years ago, their 23″ model was over $300. All three have HDMI inputs.

Asus is also now producing a couple of affordable lines of IPS monitors. The VS series includes the ASUS VS239H-P a nice looking 23″ full HD panel with a price tag of $249.99, and a smaller 22″ model (the VS229H-P) costs only $. The PB series is a bit more expensive, but offers 100% coverage of the sRGB gamut. The 23″ PB238Q currently costs $ and also features display-port, HDMI, and DVI connectors, and a USB hub (sRGB coverage of the VS model is not provided by Asus).

Long known for making excellent high-end graphics displays, DELL has also ventured into the entry-level market recently. The Ultrasharp U2312 and U2412 (23 and 24″) are good quality e-IPS displays, costing $ and . The U2312 covers approximately 95.8% of the sRGB gamut, which is good, but clearly not quite as good as the ASUS PB series.

Mid-Range IPS Monitors

If you can afford to spend a bit more money, the options open up tremendously, and the potential for enhanced performance also increases.

The new DELL U2410 is an an impressive monitor for the price. At only $540, it provides 100% sRGB coverage and 96% of AdobeRGB, with 12-bit internal processing… not to mention built in card readers, USB ports, etc. Early production models of this monitor had some dithering problems that have since been corrected with updated firmware, so they should not be a problem. Because this is a true extended-gamut monitor, operating systems prior to Windows 7 (that don’t manage your color) will make this monitor difficult to use. (Some users of this monitor complain of a pink-green shift across the screen. It’s unclear whether this is true with the newer updates of this model, as many people also claim that there is no banding or color shift. This may be a case in which you’ll have to order and replace with another unit if you have problems).

Another very popular option is the Apple 24″ Cinema Display. Apple Cinema Displays have been standard workhorses of the graphic art trade for years, and they’re one of the reasons that Macs have kept such a strong hold on the industry. They’re more expensive than some similarly performing models (around $880 for a 24″), but have a reputation for quality. Some people have reported problems with reflections on the glossy screen surface.

Professional Editing IPS Monitors

If high performance is more important to you than sticking to a tight budget, there are a few monitors that fit the bill.

The HP DreamColor LP2480zx is probably the nicest monitor that I’ve ever had the opportunity to use. It is a 10-bit monitor, covering a full 100% of the AdobeRGB color space. The difference between this monitor and the Apple Cinema Display that I’m more familiar with is clear from the first moment that I used it; I could actually see more in photos than I had previously realized was there. This does come at a price, though… about $1850.

Similarly, the Eizo ColorEdge CG241W (and related monitors such as the CG243W, etc.) is a stellar performer. If you’d like to read a full comparison between an older Eizo monitor and an Apple Cinema Display, let me direct your attention to the Luminous Landscape article that first drew my attention to Eizo monitors, here: The Eizo ColorEdge CG301W vs. The Apple 30″ Cinemadisplay. Again, the performance comes at a cost… especially if you opt for the 30 inch versions of these monitors, but even at 24″, the cost is substantial at $1900.

There are, of course, numerous other excellent monitors out there. In fact, I haven’t even mentioned the offerings from major companies like Samsung (though I left them out on purpose) and LaCie. I’ve listed some additional monitors in the table below, but I hope that everyone reading this will add their experience and input as well. I hope that this helps!

[Since there are more monitors than I can reasonably test myself, I’ve listed monitors with which I’ve had personal experience, for which I’ve heard good recommendations from reliable sources, or about which I’ve read multiple convincingly good reviews. If your favorite monitor has been left out, feel free to email me or reply to this thread with relevant info. -JMG]

| Brand | Model | Price | Screen Size / Aspect Ratio | Resolution | Pixel Pitch (Smaller is Better) | Panel Type | Response Time / Contrast Ratio | sRGB or Extended Gamut | LUT Bit Depth | % of sRGB Gamut Coverage | % of Adobe1998 RGB Gamut Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | 27" Thunderbolt Display | [aprice asin='B004YLCKYA'] | 27" | 2560 x 1440 | .233mm | IPS | 12 ms 1000:1 | sRGB | 8-bit per color | 76% (tested) | |

| Dell | Ultrasharp U2410 | [aprice asin='B00302DNZ4'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | IPS | 6 ms 1000:1 | Extended | 100% | 96% | |

| Dell | Ultrasharp U2711 | [amazon template=price&asin=B0039648BO] | 27" 16:9 | 2560 x 1440 | .233mm | IPS | 6 ms 1000:1 | Extended | 100% | 96% | |

| Dell | Ultrasharp U3011 | [aprice asin='B004KKGF1O'] | |||||||||

| Eizo | FlexScan SX2462W | [aprice asin='B004WIW8X8'] | 24" | 1920x1200 | .270mm | IPS with overdrive | 5ms grey-to-grey 850:1 | Extended | 12-bit per color | 100% | 98% |

| EIZO | ColorEdge CG241W | [aprice asin='B000T9OX78'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | VA with overdrive | 6ms 850:1 | Extended | 12-bit per color | 98% | 95% |

| EIZO | ColorEdge CG245W | $2802 | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | IPS with overdrive | 5ms 850:1 | Extended | 12-bit per color | 100% | 98% |

| EIZO | ColorEdge CG243W | [aprice asin='B002RGTFLA'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | IPS with overdrive | 5ms 850:1 | Extended | 12-bit per color | 100% | 98% |

| HP | DreamColor LP2480zx | [aprice asin='B001B0QMGE'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920x1200 | .270mm | IPS | 6 ms grey-to-grey 1000:1 | Extended | 12-bit per color | 100% | 100% |

| HP | LP2475w | [aprice asin='B001FS1LLI'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | IPS | 5ms 1000:1 | sRGB | 8-bit | not provided | not provided |

| HP | ZR22w | [aprice asin='B003D1CFHY'] | 21.5" 16:9 | 1920 x 1080 | .2475mm | S-IPS | 8ms 1000:1 | sRGB | 8-bit | not provided | not provided |

| HP | ZR24w | [aprice asin='B003D1ADUU'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | S-IPS | 7ms 1000:1 | sRGB | 8-bit | 97% | not provided |

| HP | ZR30w | [aprice asin='B003RBNMJA'] | 30" 16:10 | 2560 x 1600 | .251 | S-IPS | 7ms 1000:1 | Extended | 10-bit | 100+% | 111% (tested) |

| LaCie | 324i | $1139 | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | P-IPS | 6 ms 1000:1 | Extended | 10-bit | not provided | 98% |

| NEC | LCD3090WQXi-BK | [aprice asin='B0013DJ31A'] | 30" | 2560 x 1600 | .251 | IPS | 6ms grey to grey 1000:1 | Extended | 12-bit | 100% | 98% |

| NEC | P221W | [aprice asin='B001IWOB86'] | 22" | 1680 x 1050 | .282 | 8ms grey to grey 1000:1 | Extended | 10-bit | not provided | 96% | |

| NEC | LCD2490WUXi2-BK | [aprice asin='B002C9KAO8'] | 24" 16:10 | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | IPS | 8ms grey to grey 1000:1 | sRGB | 12-bit | 97% | 75% |

| NEC | PA271W | [aprice asin='B003LD1QRY'] | 27" 16:9 | 2560 x 1440 | .233mm | IPS | 7ms grey to grey | Extended | 14-bit | 100% | 97.1% |

| NEC | PA241W | [aprice asin='B0036V76NY'] | 24" | 1920 x 1200 | .27mm | IPS | 8ms grey to grey 1000:1 | Extended | 14-bit | 100% | 98% |

| NEC | PA231w | [aprice asin='B0047T7NQ4'] | 23" | 1920 x 1080 | .265 | IPS | 8ms grey to grey 1000:1 | Extended | 14-bit | - | - |

| Viewsonic | VP2365wb | [aprice asin='B002R0JJYO'] | 23" | 1920x1080 | .265 | IPS | 14 ms 1000:1 | sRGB | 8-bit | - | - |

Additional Necessities

If you’re going to spend the money to get a good quality display, you’ll also need a color calibration system for it. In fact, this is true no matter what monitor you’re using… but it would be especially wasteful not to calibrate a high quality display. These can be quite inexpensive, and there are a variety of choices. Most high-end monitors are bundled with a colorimeter already. The Spyder models range in price from about $85 to a couple hundred, as do the models from X-rite, like the ColorMunki ($500) and Eye-One LT ($150).

It also makes sense to create color profiles for your camera using something like an X-Rite Color checker. It can dramatically improve the color accuracy of your photos, and is quite simple (see the videos here).

Additionally, you should keep in mind that some of these monitors use 10-bit or higher technology, and require specific graphics cards, and in some cases, the DisplayPort connector must be used rather than the standard digital output or HDMI. If you expect to use 10-bit or higher display technology, check with the monitor manufacturer to see what graphics cards are supported.

[If you’d like further information about building a computer specifically for Photo Editing, please see my article on Choosing the Best Computer for Photo Editing – JMG]