Nikon didn’t come out and say it. In fact, they claim that they will continue development of their DSLR camera line, and I don’t doubt it. They also still produce the F6 35mm film-camera. But with Nikon’s official announcement of a full-frame mirrorless camera line and new lens mount, all SLRs are now passengers on a sinking ship.

Nikon has been losing market share over the past few years while Sony and their legion of mirrorless cameras have been gaining ground, and waves of Fuji mirrorless cameras have been greeted with open arms by photographers around the world.

Sony’s mirrorless, full-frame cameras recently surpassed sales of Canon and Nikon models in the USA, making them the top selling full-frame cameras, mirrorless or otherwise1 Canon still maintains about 50% of the interchangeable lens camera market share, with a combination of full-frame and APS-C cameras . In China’s mammoth market, Sony had already topped Canon and Nikon earlier in the year, and Sony had overtaken Nikon’s No.2 spot a year ago in Japan. In Germany, Sony first reported in 2015 that their A7 camera line held a lead in sales over Canon and Nikon full-frame DSLRs.

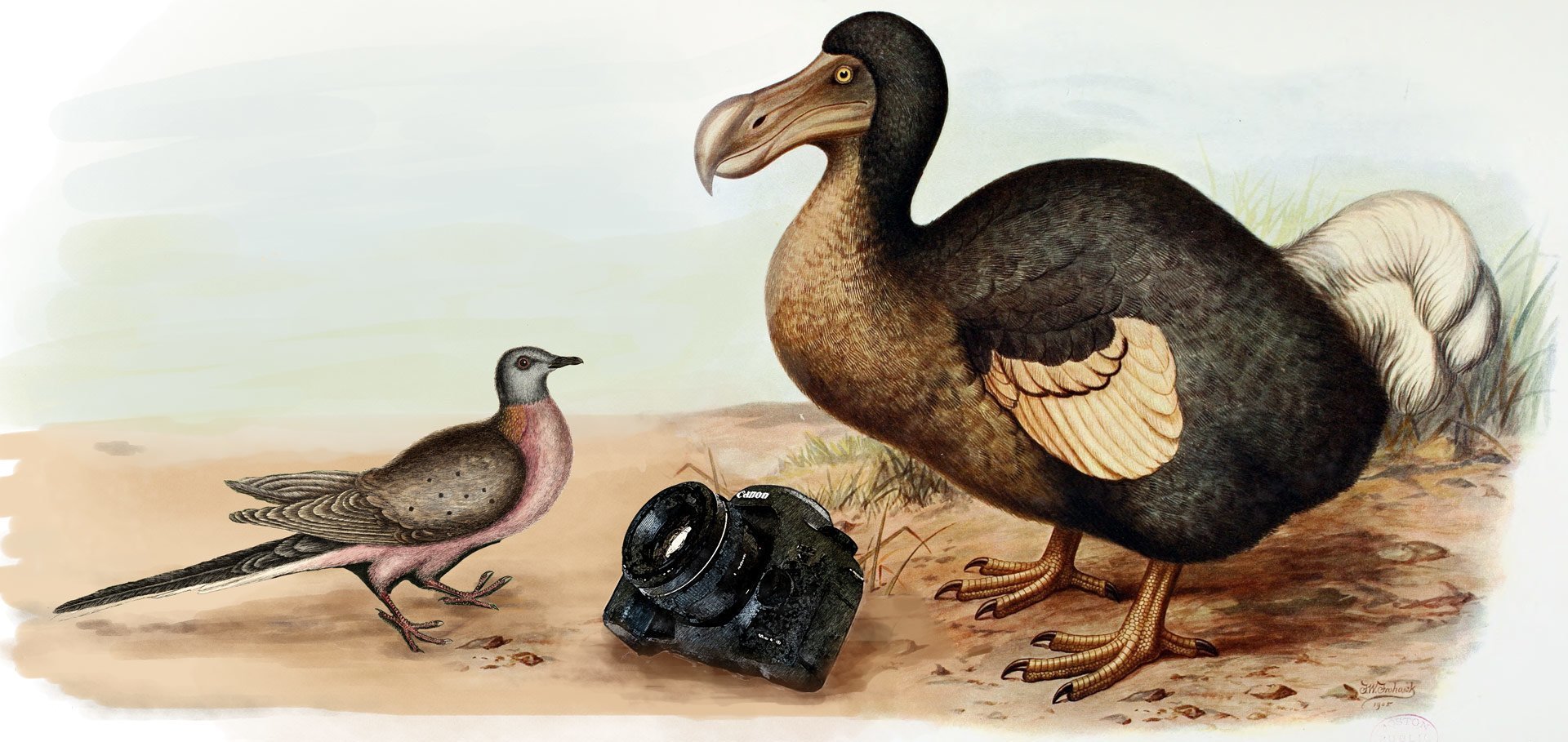

With Nikon’s announcement, Canon will have no choice but to come to the market with their own full-frame mirrorless cameras, though they’ve been dragging their feet for years, claiming that mirrorless autofocus systems are not ready for professional use. Sony’s A9, Fuji’s X-T2 and a decade of micro4/3 camera AF development would all beg to differ. And when Sony, Canon and Nikon are all producing full-frame and APS-C mirrorless lines, digital SLRs wills will take up residence with the dodo and the passenger pigeon.

Mirrorless systems are no longer a novelty like the pellicle mirror cameras that have been trotted out periodically since the 1960s2 Sony’s SLT digital cameras sold over the past decade were only the latest in a long string of pellicle mirror cameras. In the 1990s, Canon’s EOS RT and a special version of the EOS1N used pellicle mirrors in cameras marketed towards action photographers, and decades previously the Canon Pellix camera used the same technology before SLRs had gained widespread acceptance. . Mirrorless cameras offer a reliable solution to one of the main problems that has driven change in camera design since the invention of the camera: how do you see what your photo will look like before you take it?

Each revolution in camera design has come with a new method of framing and focusing the image.

With the earliest view-cameras, photographers huddled under a shade cloth to look at a dim image that was projected directly through the camera from the lens, creating an upside-down image on a ground-glass focusing screen. But when it came time to take the photo, a film plate (or sheet) had to be inserted into the camera, blocking the view completely. Not very practical for most of us, though some photographers still work this way.

As cameras got smaller and more portable, many large format and medium format cameras started using viewfinders that didn’t pass through the camera lens at all, and only gave users an approximate idea of what would be included in the photograph, but were quick and easy to use. Some contained simple optics, while others were no more than a simple wire frame. Focus was often set by approximating distance to the subject.

In smaller, 35mm format cameras, rangefinders became increasingly popular until the 1960s. Rangefinders such as the ones found in Leica and Contax cameras allow photographers to focus accurately, but since the rangefinder’s perspective is not through the camera’s lens, framing is still approximate. Twin lens reflex cameras worked on the same principle; photographers looked through a second, parallel lens to set focus, but framing was still not exact, and lenses were not interchangeable on many of them3 It turns out that Mamiya made TLR cameras with interchangeable lenses. Thanks to Ian for pointing out this oversight; originally I had stated that they were not interchangeable (updated 8/21/18) .

Single-Lens Reflex (SLR) cameras have been around since the 1930s, but technical problems kept them from the mainstream market for half a century. SLRs solved the focusing and parallax problem that persisted in all other cameras by using a mirror to allow the photographer to look through the camera’s lens.

Problems posed by the delicate mechanisms to make the mirror quickly and reliably flip out of the way when the photo was taken, and at the same time make the aperture diaphragm in the lens stop down, were not easy to solve. However, in 1959, Canon and Nikon both introduced their first SLR systems, and the rest is history. Within a decade, SLRs dominated the market for professional 35mm photographers… except for Leica shooters.

Why the Takeover of Mirrorless?

Why did Leica shooters stick with range-finders? One of the reasons4 Others will point to the quality of their optics. Cynics will point to the perceived status of owning the extraordinarily expensive brand as a fashion accessory. is that their mirrorless design allowed them to be smaller, lighter, quieter, and (with fewer moving parts) more reliable. Additionally, Leica lenses were able to circumvent the optical design problems caused by the gap between the lens and the film caused by the SLR mirror-box, and are therefore often much smaller than typical SLR lenses.

Mirrorless digital cameras also solve these problems, and at the same time solve the problem that persisted in rangefinders: inaccurate viewfinder coverage.

Mirrorless digital cameras also solve these problems, and at the same time solve the problem that persisted in rangefinders: inaccurate viewfinder coverage. With mirrorless, we see the image exactly as the sensor does because we’re looking through the sensor. Like rangefinders, camera bodies can be smaller and quieter (completely silent when using an electronic shutter), and wide to mid-angle lenses can be much smaller (though these haven’t materialized just yet for full-frame cameras). Without a mirror to flip up and return between exposures, frame-rates can also be much higher (the Sony A9 gives us 20fps), and the vibrations associated with mirror-movement are no longer a concern.

Autofocus SLRs have suffered from another problem: focus accuracy. Have you ever had to set the micro-focus adjustment on your camera for a particular lens? This is because SLR autofocus5 At least, phase-detection autofocus, which is the method we all use most of the time is controlled by a separate focusing module that is mounted somewhere in the mirror-box, not on the sensor. It sets focus based on a prediction of how the lens will focus on the sensor when the mirror flips out of the way. But it’s not always accurate. Some lenses don’t focus where expected, and SLR owners need to set micro-focus adjustments in their cameras or with lens-docks like those made by Tamron and Sigma. Worse, some lenses focus correctly on far away subjects, for example, but not on closer ones, so simple micro-adjustments can’t fix the problems completely.

Micro-adjustments will never be a problem with mirrorless digital cameras because focusing is not predictive, it is direct: the camera focuses with the actual image that the lens projects onto the sensor.

Every solution to the preview/focus problem with cameras has always had it’s drawbacks, and mirrorless digital is no different. These are a few of the main problems with the system:

- Battery Drain: an electronic viewfinder (EVF) is required to use a mirrorless camera, and they drain batteries quickly, whether you’re taking photos or just looking.

- EVFs have limited resolution and dynamic range

- EVFs are not real-time; there’s always at least a minuscule delay between the sensor reading the image and the EVF displaying it (though mirror flip-up also causes a delay in SLRs).

- Mirrorless focusing systems are still catching up with SLRs.

In practical terms, EVF lag and resolution limits are not major concerns, and EVFs can sometimes improve visibility over optical viewfinders.

The state of mirrorless autofocus is a matter of debate, currently, but will only improve in the coming years. My current Sony A7RIII focuses just as well or better than my Canon 5D III did, except in one situation: zooming during autofocus. This is a problem to be overcome, but there’s no theoretical reason that it can’t be.

Battery drain is a serious concern, especially for photographers working in remote locations or photojournalists working in conflict areas where power may be scarce.

On balance, then, mirrorless cameras solve the two main problems (focus and preview) without introducing significant new ones.

here will always be a few stragglers, but the time of SLRs is now coming to an end, just as the ages of large format box cameras, twin-lens reflex cameras and, indeed, film cameras have come and gone. I, for one, have loved my SLRs over the years, and will probably feel a bit nostalgic as they are moved from camera bags to museum shelves (or thrift shop shelves, perhaps), but as a photographer, I’m excited about the mirrorless cameras to come and the problems that they will solve.

Are you ready for the mirrorless era? Let me know in the comment section below!

Graphics in this article are based off of public domain photographs from the National Museum of American History and public domain prints, including “In the Well of the Great Wave Off Kanagawa” by Hokusai, Frohawk’s dodo, and Catesby’s passenger pigeon.