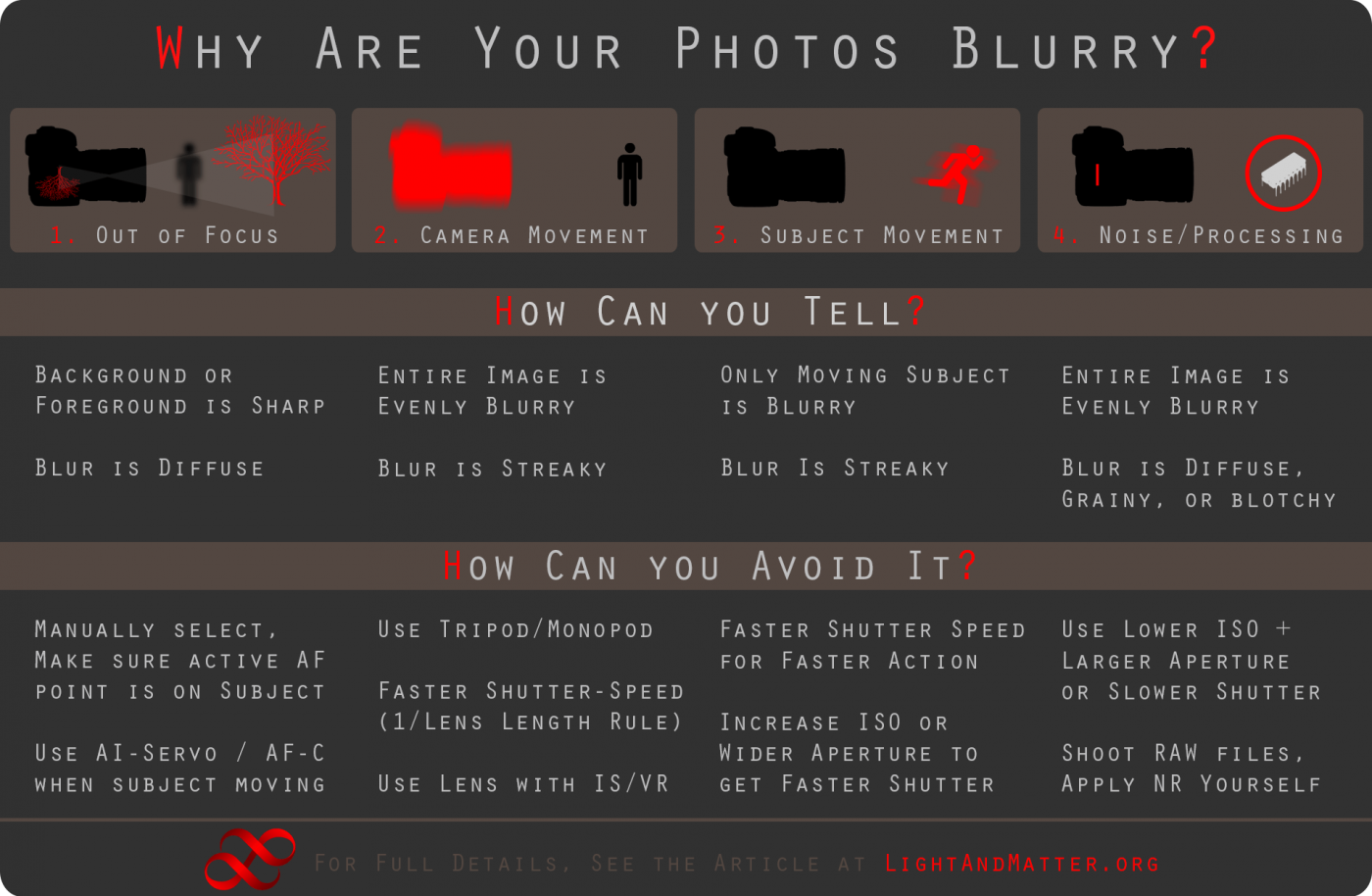

3. Subject Movement

This is what we usually think of when we think of “motion blur”. When your camera is not using a fast enough shutter speed to freeze action, moving objects in your picture will be blurry.

How Can You Tell?

When subject movement is the problem, only part of your image will be blurry. If you’re taking a photo of an athlete, for example, the fastest moving parts of the person (feet, hands, forearms, and lower legs) will be the most blurry, slower moving parts will be less blurry, and the ground or other stationary objects should be sharp (assuming that they are also in focus and there’s no camera shake).

Examples:

How Do You Avoid It?

There are two ways to avoid motion blur: first, by using a sufficiently fast shutter speed, and second, by lighting your photo entirely with a flash (or multiple flashes) and using ANY shutter speed. Note that using a lens with image stabilization or a tripod does not help.

As a general rule, if you’re taking sports pictures, you’ll need to use a shutter speed of at least 1/500th of a second. This will stop most action, but the fastest moving parts of the subject may still be slightly blurry. A shutter speed of 1/1000th or faster is ideal, and will stop nearly anything.

For slower moving action, 1/250th is usually fine. It’s also enough for catching a “peak” action. “Peak” actions are found when, for example, a player is jumping up to catch a ball: there will be a moment when they’ve stopped rising and are beginning to fall, and during that “peak”, they’re stopped or moving very slowly. Many sports have this type of action at some point, and it can be useful to try to catch it when you’ve exhausted your options to get a faster shutter speed.

There are a couple of way to get your camera to use its fastest shutter speed. Most commonly, I set the camera to Aperture Priority (again, Av on Canon, A on Nikon), and open the aperture as wide as possible to let in lots of light. This will provide the fastest shutter speed possible while still giving a correct exposure. You can also use Shutter Priority (Tv on Canon, S on the Nikon dial) and set the shutter speed directly to the setting you need, but if the aperture can’t open wide enough, you may under-expose your images (or, if you use auto-ISO, you may end up with very noisy images). Again, if you don’t have a firm understanding of how these changes affect your picture, I recommend watching my video (only 8 minutes long) about the Three Basics of Exposure.

Using a flash to stop action is possible when the flash is the only light that is contributing to the exposure (ie, if it’s dark enough otherwise that if you took a picture with the same setting and no flash, the resulting picture would come out black or mostly black). If ambient light isn’t getting recorded, then it doesn’t matter how long the exposure is… the shutter is as good as closed, except while the flash goes off. This means that the duration of the flash becomes the effective shutter speed, and flashes are fast— usually between 1/1000th sec. and 1/128,000th sec. or faster. That’s bullet stopping speed. Flash can be very useful if you’re shooting night sports outdoors, or most sports indoors, if you have powerful (or multiple) flash units.

PREV. PAGE NEXT PAGE