After generating quite a bit of excitement last June, Lytro finally announced the upcoming release of their light-field camera, due sometime in early 2012. If you missed the details the first time around, light-field technology allows the user to take a photo and then focus (and re-focus) the image later, using the camera’s software. As a technological feat, this is truly amazing and unlike anything seen before in traditional photography. As a consumer product, though, the Lytro Camera has some major drawbacks. This may be an instance in which cool technology can outweigh the practicality of the product. Time will tell, but Lytro is reporting a high demand for the cameras that they have currently started pre-selling through their own website for either $399 or $499, depending on storage capacity.

The Camera

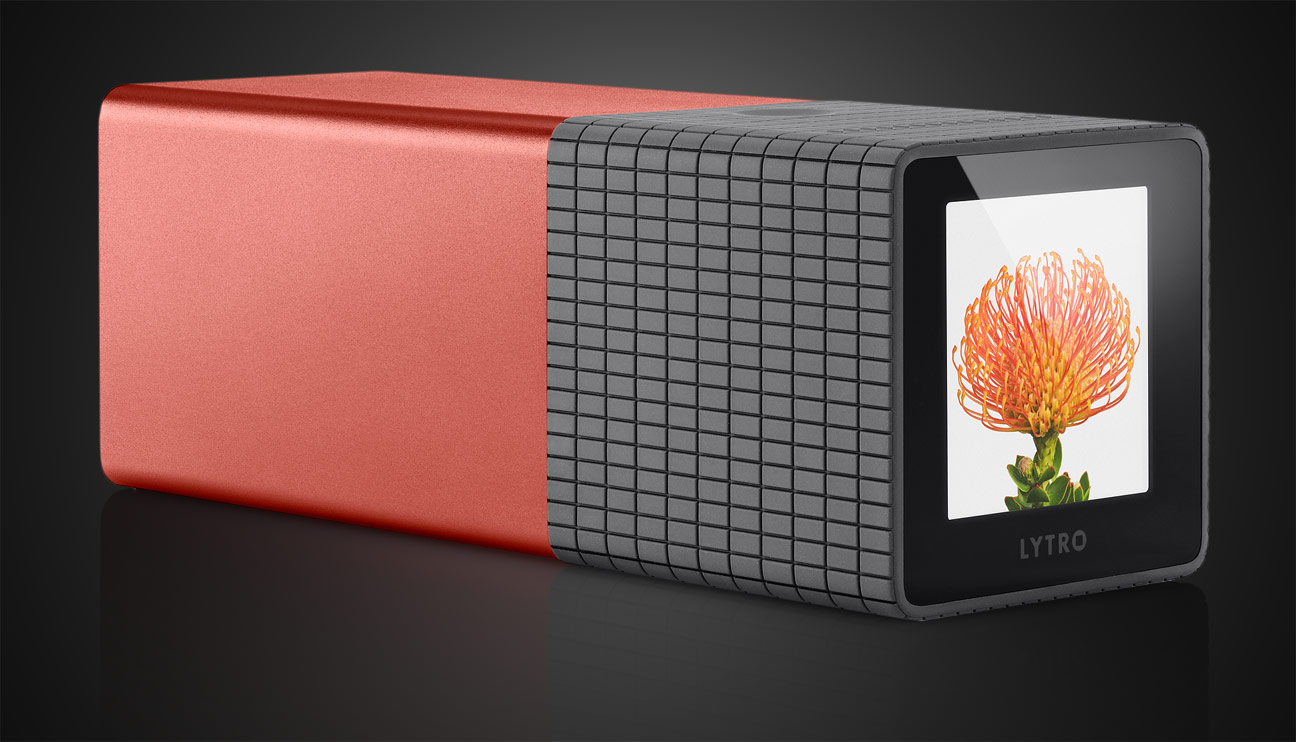

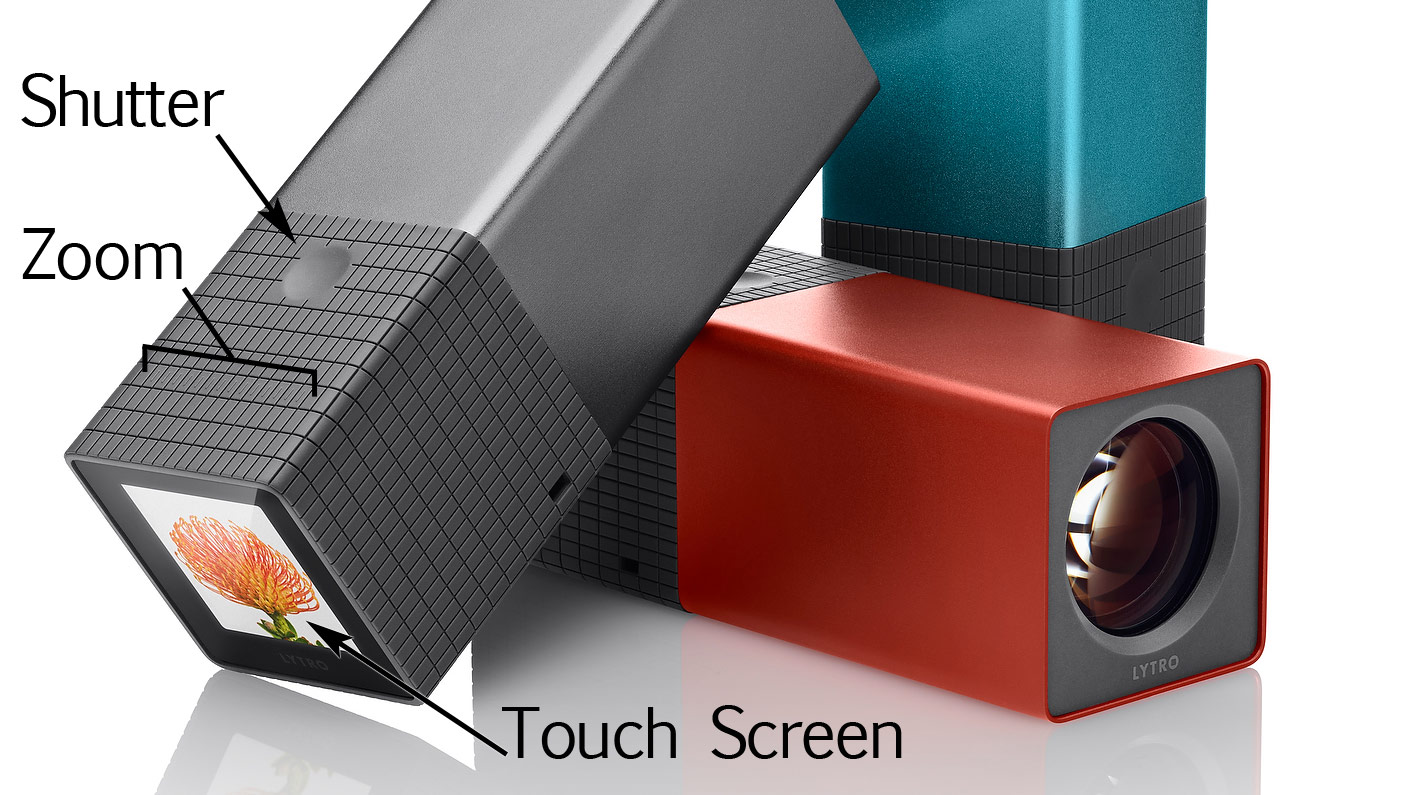

The Lytro Camera is, if nothing else, simple. Its body consists of a square aluminum tube with a rubberized grip. One end of the tube houses the lens, a fast f/2.0 model with 8x zoom (though the exact focal lengths remain mysterious) , while the other end frames a 1.4″ square touch-screen LCD. In fact, there are only three controls: the shutter release button, a zoom slider, and the LCD, which can be touched to set the exposure. You can’t adjust shutter-speed, aperture, or ISO directly, and there are no choices of shooting-modes. While the simplicity may be refreshing to those who have been frustrated by the increasingly complex digital cameras produced today, it will undoubtedly be less satisfying for photography enthusiasts who want more control. And flash photography is not an option.

In fact, the design seems to follow the iPad model. It is solidly built, with a minimum of controls. The battery is internal, and the camera can be purchased with either 8 or 16 GB of internal flash memory, both maintained via a micro-USB socket on the bottom of the camera.

The Advantages

The advantages of using a light-field camera can be summed up by viewing an example of the results:

(no longer hosted)

In fact, once you’ve seen a single example, it’s hard not to spend half an hour browsing through the entire gallery of “living-images” in the Lytro gallery. As an added bonus, when you purchase a Lytro Camera, you’re provided with living-image hosting on Lytro’s servers as well, so that you can share your images online without having to maintain your own website. No matter what else can be said about the Lytro, there will be a “wow!” factor for those who post their facebook photos as “living-images” for months. Maybe years.

The Drawbacks

As impressive as the technology is, there are still technical limitations, though. In the example above [now defunct] you’ll notice that the trees in the extreme distance are never quite in-focus, and this seems to be a common issue. You’ll also probably notice that where the branches are set against the sky, there is a significant amount of magenta fringing (chromatic aberration), and while this is common with many traditional consumer-level cameras, it is rarely visible at such low resolution.

Because of the unique image-file format, editing is limited to the dedicated Lytro software. And “editing” is a bit of a stretch. The square image can not be cropped, adjusted for color or exposure, sharpened, or otherwise filtered. You can’t increase the depth of field, which seems as though it should be a possibility, since the data is all there. In fact, the software merely allows you to rotate the image and add captions. And even these limited options are only available if you own a Mac. A PC version will be available in the future.

And suppose you want a print of your photo, now that you’ve focused in on the proper part of the image. The resolution of the output is 1080 x 1080 pixels, a great fit for a full HD television, but at 1.16 megapixels, even a 6×6″ image will be pushing the limits of acceptable quality for most people.

Further Thoughts

Moreover, the lack of sharp focus in the distant background makes me wonder exactly how much of what’s going on is light-field technology, and how much could be software trickery. If we consider how small a 1 megapixel sensor could be (that resolution is much lower than what is found in the cheapest cell phone camera sensors today), the depth of field could be very deep to begin with. If a good lens were pre-focused to the hyperfocal distance for a scene stretching from a few feet away to infinity (or a little closer than that, considering that infinity is not quite sharp), the depth of field of such a small sensor could potentially hold most of that distance sharp anyway. If that were the case here, then the Lytro Camera might only be limiting focus by adding blur with software based on distance, and allowing the user to move it around. Even that would be a significant technological development, but not one with the same promise for future development, and I think that many of us would feel cheated.

The light-field concept could raise some interesting intellectual property issues in the future as well. If a day came when professional journalists were submitting photos to their editors in light-field format, allowing the editors to choose the focal plane, who has created the image? Does the editor also deserve credit as a co-photographer or artist? Did the photographer see the same image? It would be interesting to see how publications would work that out.

However we feel about the current state of the technology, it is undeniable that light-field theory has opened up an entirely new horizon for the development of imaging technology. I can’t wait to see how things turn out!