When I got interested in photojournalism in the early 1990s, there were only two real players in the market (at least, in my price range), and that made my choice a bit easier. Nikon and Canon. Sure, Minolta was out there, Pentax and even Sigma had AF SLRs, but because they didn’t have professional bodies, they were not really in the running. For years afterward, I ignored most of the remainder of the SLR market.

Sony’s introduction of the Alpha A900 changed that. Here was a professional quality body with a professional quality sensor (the same as that from the Nikon D3x), and at a reasonable price (compared to the Nikon, at any rate). And then came the Carl Zeiss lenses, made specifically for Sony. I actually began meeting professional photographers who were Sony shooters, and they weren’t ashamed to admit it. The Sony Alpha a850, also weighing in with a 24.6megapixel sensor at under $2000, extended Sony’s influence even further.

In the same way, Sony’s A55 and it’s little brother the A33 have the potential to make a mark on the amateur market. They’re two of the most innovative new SLRs in years, especially for entry level models. Let me begin by taking a look at some of their features. [Sony, incidentally, has been calling them SLTs instead of SLRs because the mirror transmits light. This is just needless confusion; the term ‘reflex’ in SLR has nothing to do with the movement of the mirror.]

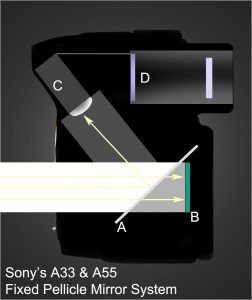

Undoubtedly the most remarkable feature of the A55 and A33 is the implementation of a fixed pellicle mirror. In the vast majority of SLRs, when you look through the viewfinder you’re actually looking down through a tiny periscope; the light comes in through the lens, then is reflected off of a mirror up into the prism of the viewfinder, which reflects the light out into your eye. However, when you release the shutter, the mirror has to flip up so that the light can get to the film or sensor instead. This process not only takes time, but it introduces noise and vibration into the system, both of which can be problematic.

A fixed pellicle mirror, though, solves these problems. Instead of using a mirror that flips up and out of the way, fixed-mirror systems use a thin, semi-transparent mirror that lets most of the light through to the film/sensor, while reflecting another portion of it up to the viewfinder. Thus, when the shutter is released, there is no delay for the mirror to get out of the way; the shutter can release immediately. Furthermore, since the mirror stays in place, you don’t lose your view through the lens during the exposure. This not only helps the camera maintain focus, but helps the photographer track his/her subject. I first encountered this type of setup in a Canon EOS1 RS back in the mid-1990s. The cameras were extremely fast for their day, shooting 10 frames per second. However, the cameras never gained popularity due to a couple of drawbacks: since only part of the light got to the film, you essentially lost the advantage of using expensive, wide aperture lenses. The EOS1 RS, if I’m not mistaken, lost 2/3rds of a stop. This means that if you’re using a 50mm f1.4 ($350) lens, you have to expose as if you were using a 50mm f1.8 ($98). Furthermore, since only about 66% of the light coming through the lens was directed to the viewfinder, it was difficult to see all of the detail, and nearly impossible to use in the dark.

The new Sonys are capable of very fast shooting, as would be expected, but there’s also an advantage that’s never been encountered before in a fixed mirror SLR: full time, high quality auto-focus for HD video. Naturally, that capability extends to still-photography as well.

Additional Features

Like most Sony SLRs, these bodies include image stabilization known as “Steadyshot Inside”. Unlike Canon and Nikon cameras, which offload the responsibility to the lenses, Sony bodies provide somewhere in the range of 2-4 stops of stability, and works with any lens put on the camera. The a55 also has built-in GPS for geo-tagging, which I’ve always thought should be a standard feature, now that the technology is so prevalent. Like the Canon 60D, it has an articulated rear LCD.

Comparison with Canon and Nikon

Canon’s “Rebel” series is the most popular line of entry-level DSLRs in the United States, and the Nikon D3100 is a very sophisticated new model from Nikon, so they seem like reasonable models with which to begin a comparison. First, a look at the standard features:

| Sony Alpha a55 | Canon Rebel T2i / 550D | Nikon D3100 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Price | $749 | $715 | $626 |

B&H Price  | $749 | $719 | $649 |

| Body Material | Polycarbonate | Polycarbonate, Fiberglass Resin and Stainless Steel | Polycarbonate |

| LCD Size / Resolution | 3.0" 921,000 pixels | 3.0" 1,040,000 pixels | 3.o" 230,000 |

| LCD Articulated? | Yes | No | No |

| Sensor Size | 15.6mm x 23.5 | 14.9 x 22.3mm (APS-C) | 15.4 x 23.1mm |

| Crop Factor | 1.5x | 1.6x | 1.5 |

| Sensor Resolution | 16.2 Megapixels | 18 Megapixels | 14.2 |

| ISO Range | 100 - 12800 | 100-6400 +12800 | 100-3200 +6400 +12800 |

| Total AF Focus Points | 15 | 9 | 11 |

| Cross-Type AF Sensors | 3 | 1 | ? |

| AF Light Level Range | -1 to +18 | -.05 to +18 EV | -1 to +19 |

| Metering System | 1200 Zone evaluative metering | 63 Zone Point Linked Evaluative 9% Center Weighted 4% Spot | 420 pixel RGB sensor evaluative 6% Center Weighted 2.5% Spot |

| Max Frame Rate : RAW (14-bit) | ? | 3.7 | ? |

| Max Frame Rate : RAW (12-bit) | n/a | n/a | ? |

| Max Frame Rate : JPG | 10fps | 3.7fps | 3fps |

| Max Burst Duration RAW (at highest frame rate) | 20 | 6 | ? |

| Max Burst Duration JPG (at highest frame rate) | 35 | 34 | ? |

| Shutter Speed Range | 1/4000th - 30 sec. +bulb | 1/4000th - 30 sec. +bulb | 1/4000th - 30 sec. +bulb |

| Maximum Flash Sync Shutter Speed (standard flash) | 1/160th sec. | 1/200th sec. | 1/200th sec. |

| HD Video Resolutions | 1080i, 1080p, 720p | 1080p, 720p | 1080p, 720p |

| Available HD Video Frame Rates | 1080i @ 60fps 1080p@ 30fps (no 24fps yet) | PAL and NTSC 24/25, 30 at 1080p 24/25, 30, 60 at 720p | 24fps @ 1080p 24 or 30 fps @720p |

| Auto Focus in Video Mode | Phase Detection | Contrast Detection | |

| Firmware Sidecar Available | No | Magic Lantern Under Development. Currently version provides audio meters. | No |

| Media Type | SD / SDHC / SDXC plus Sony memory sticks. | SD / SDHC / SDXC | SD / SDHC / SDXC |

| Weight | 492g (with battery and SD Card) | 530g (with battery and SD card) | 455 (body only) |

| Viewfinder Coverage | 100% 1.1x magnification, 1.4 million pixel viewfinder (electronic) | 95% 0.87x magnification | 95% .80x |

Major Issues:

Battery Life

I mentioned before that Sony’s implementation of the fixed pellicle system has some drawbacks. There will always be a loss of light with this camera, but only about a third of a stop. For most entry-level photographers, I don’t think this will be an issue. With modern digital cameras, increasing the ISO 1/3rd stop will not produce a significant difference in noise. This is a minor drawback, as far as I’m concerned.

The major one is power draw. Although Sony reports that you can take a few hundred photos on a battery charge, the numbers are misleading; many photographers have found that when using the camera for extended periods (such as shooting a long event), even when not releasing the shutter, the draw of the electronic viewfinder kills the battery in just a few hours. In fact, using the electronic viewfinder uses more power than using the rear LCD in live-view mode (330 vs 380 expected photos, according to Sony)! Reports vary, and a systematic testing approach isn’t obvious, but most owners don’t expect to be able to use a battery for more than about 3 hours. This shouldn’t be a problem for casual photographers, or even photographers who plan ahead and carry an extra battery or two. I can imagine it being a very significant problem for backpackers and landscape photographers who spend a long time away from a power supply. Standard SLRs, such as the Canon T2i or Nikon D3100, will generally shoot about the same number of photos per battery charge (450 or so without using live-mode), but the photographer can spend days staring through the viewfinder, waiting for the right moment to click without causing a dramatic drain on the battery.

There will undoubtedly be photographers who object to the electronic viewfinder, period. Personally, I think it has some great advantages as well, so I’ll let it stand as a matter of taste. It does seem to provide a good representation of what the sensor will capture, at a larger size than most APS-C viewfinders (including the Canon and Nikon), and it’s nice in the dark.

Full Time Autofocus

The Canon T2i doesn’t have full-time autofocus in video mode. Nikon’s D3100 does offer full time AF like that of the Nikon D7000, but it’s the slow, contrast-detection type. Sony is the only model that offers full-speed, camcorder style AF during video recording. This is a big deal for people who want to shoot videos on their SLRs in the same way that they would with a camcorder or point and shoot; so far, this hasn’t been possible. Victory for Sony.

The same can be said for shooting fast bursts of action in still photography. Although some pro-model cameras (Canon 1D IV) can shoot 10fps, it’s an unheard-of speed for a camera in this price range, and even pro-models do not focus full time during their bursts, they use predictive focusing instead (which actually works quite well, for what it’s worth).

Video Issues

For serious film-makers, the Sony won’t be such a big hit. Unfortunately, it has very limited manual control in video mode, and its automatically controlled exposure sometimes leaves a lot to be desired (like when it cranks the ISO up to 1600 for no good reason). The a55 also doesn’t support 24fps shooting.

However, Sony has already announced that they plan to offer a firmware upgrade for the a55 to improve the manual control and other video options for the camera, so perhaps it will have a brighter future.

Ergonomics

I usually leave ergonomics out of my articles completely, since it’s such a subjective issue. However, I have to mention this: the Sony a55 is small. It’s quite small, actually. For me, it’s uncomfortably small. I don’t have massive hands, but I do have long fingers, and I felt that I could only comfortably fit three of them on the camera body. In this regard, the Canon and the Nikon are not particularly comfortable either, but both are better than the Sony.

Conclusions: Who Should Buy the a55?

The Sony a55 is not for everyone, but it is still a very remarkable and capable camera. The camera’s features benefit two main user groups. The first is action photographers; primarily sports photographers rather than field journalists. The continuous auto-focus system, the continuous visibility, the fast response, and the fast bursts will all benefit action photographers. Because there are only 3 cross type-points for focusing, it may not perform as well as more professionally oriented models, but it should certainly out-shoot the entry-level competition. The lack of mirror movement also makes it a good choice for photographers interested in macro photography, especially for insects or other moving objects for which mirror-lock-up on competing models is impractical.

The second group is the video enthusiast, but not the serious film-maker. That is, a person who is interested in using the camera as an alternative to a home video camera or point-and-shoot camera, but not necessarily for film or broadcast production work. The AF system makes the camera the first great alternative to a video camera for the casual user, but the lack of manual controls keep it out of the range of the more serious user.

I would not recommend the camera for the landscape photographer who spends extended periods away from home, the car, or nearest power supply. This is unfortunate, because the built-in GPS would be great for hikers who want to keep track of locations, but the number of batteries that you’d need to carry for a multi-day trip would simply be beyond the realm of practicality.

And naturally, if you’re buying your first SLR, you should consider that your camera is part of a larger system, including lenses, flash equipment, software, and potentially, 3rd party extras. Some flash radio-triggers that offer TTL, for example, are manufacturer specific and Sony has a small enough segment of the market that they’re not always supported.

[ As usual, questions and comments are welcome! If you’ve used a particular camera and can offer insight, please feel free to share your thoughts. ]